Frishta held two thermos flasks of green tea and three plastic trays of sugar-coated almondsand chocolates, and placed one tray before Mour on the Afghan rug, and the other two on the oak table in front of Agha and me. Poured the steaming tea into cups and placed them next to the trays. I uttered manana – the rocket carrying Brigadier and Agha had landed on the BBC News planet. Frishta smiled and said a ‘mention not’.

Frishta sat next to Brigadier on the worn-out sofa opposite me, and leaned her ears to the portable radio. I’d said nothing about today’s incidents to my parents, and, to my relief, neither Brigadier nor Frishta mentioned Rashid or the Khalqi agent. Frishta had suffered a ‘nasty fall’ when Agha asked her earlier about the bruised eye. I yearned to discover Rashid’s fate, but waited with a tightened chest for Frishta, who chipped in with a comment or a question about the news.

Mour whispered something to Mahjan, who sat opposite Mour on the mattress. Mahjan tiptoed by Brigadier, pulled the brown curtains and opened the window of the orange-lit lounge. The black sky revealed itself. The faeces smell nevertheless persisted.

I reckoned Frishta got bored once her questions and comments fell on deaf ears, and she sat next to Nazo on the mattress, handing my sister a cow chocolate. ‘How are your studies?’

‘OK,’ Nazo mumbled and peeped at Mour. She touched Frishta’s buckles. ‘What’s this?’

‘Push-ups from the gym.’

‘What gym?’ Nazo ate the chocolate. I unwrapped one and put it in my mouth.

‘Judo.’

‘Really?’ Nazo said.

My hair stood on end. I knew no jelai who attended a gym, let alone a fighting one. How come I’d missed those knuckles, hard like marbles?

‘You let your daughter go to the gym?’ Mour said to Mahjan, frowning.

‘Brigadier says if a son can do it, why not a daughter?’ Mahjan said and pushed back the antenna on the bulky television.

‘Does he not think about her future?’

‘What’s wrong with going to the gym, tror jan?’ Frishta asked.

I chewed the chocolate and sipped my tea, not knowing why Mour would again waste time arguing with a stubborn jelai.

‘Wrestling, jumping, climbing trees, even screaming: all these acts can damage virginity,’ Mour said.

‘Scientifically it’s untrue.’

Mour gave an exasperated look towards Mahjan. Someone outside on a flute played the Let’s Go to Mazar tune.

‘Haleks do them all,’ Frishta added.

‘Jelais are meant to take care of their virginity. They carry the ezat of the family.’

Why did other people’s behaviour trouble Mour? It was up to Frishta how to live her life.

‘Do haleks not have virginity?’ Frishta said.

‘Haleks are born differently.’

‘So only we have to “carry the ezat of the family”?’

‘We’re also required to stay virtuous,’ I said.

‘A jelai loses the chance to marry if she loses her virginity,’ Mour said, raising her eyebrows. ‘She may be able to marry a widower or become a second wife if the loss isn’t due to sinful behaviour.’

‘Would a halek in a similar situation marry a widow?’

‘Haleks don’t have virginity.’

‘Do you accept such unfair rules, tror jan?’ The flute stopped.

‘Breaking these Pashtunwali rules ruins reputations and destroys futures.’

‘I won’t sacrifice today for a better tomorrow.’

Mour’s eyes rolled to Mahjan, who told Frishta to stop the ‘nonsense’ and asked Mour to drink her tea.

Zarghuna rushed in and informed us of Safi having pooped in his pants. She dashed out. Some of those pants may have lain behind the sofa Agha and I sat on.

Mour told Zarghuna in a raised voice to keep it quiet, asking Nazo to check on her sister. Nazo rushed out. Cold coming from the open windows: the nappies smell and the heated debate made the room as boring as the first day of school. If only we had left for our homes.

‘Tror jan, bring your daughters up as strong as your son. Instilling in them that they bear the responsibility of the family’s ezat makes them weak. Do you ever tell Ahmad jan to “take good care of yourself because you’re the ezat of the family”?’

I chipped in and told Frishta that Mour advised me that if I committed the five sins of alcohol, drugs, gambling, womanising and mingling with bad friends, I’d burn down my life and the family name to a small pool of wax. To cool off the argument, I went on, Mour further advised me to plan for tomorrow, spend within my budget, think of providing halal for my family, respect my elders, care for my sisters and future wife, and be kind to my children.

Frishta shut up, and I handed her seven of my year eight notebooks. A dog howled, followed by another. Agha and Brigadier looked at each other; maybe the mujahideen popped up here, too. They recently crept at night-time into other parts of Kabul and assassinated government officials. Mr Barmak, the ground-floor neighbour, yelled a shoo. Visibly relieved, Agha and Brigadier carried on listening to the radio while Frishta kept skipping through my notebooks.

She thanked me and requested we worked in a separate room because she couldn’t concentrate in the lounge when Agha and Brigadier talked about politics, and, though she didn’t mention it, Mour threw troubling comments.

‘My notes are self-explanatory.’

‘Ahmad has his own studies,’ Mour said to Frishta.

‘It’s just for an hour every day. Inshallah, it’ll be over in a few weeks,’ Frishta said.

‘Frishta really needs your help, zoya,’ Mahjan said.

I counted half a dozen colours in the room: Brigadier’s sofa was black, mine and Agha’s brown; Mour’s mattress red, Mahjan’s yellow; the walls purple; and the television walnut.

‘It’ll mean a lot to me, Ahmad jan,’ Frishta said.

‘I’ve got my own studies,’ I said, detesting being pressurised into doing something improper. I wished I had the choice to get out of this prison.

Frishta’s eyes welled up. Mahjan told her not to worry; she could seek someone else’s assistance. Frishta cleared her eyes and mumbled an ‘OK’.

What I feared all along happened. Agha turned down the radio and inquired into the matter.

Mahjan explained.

‘Who’s she supposed to seek help from, if not you?’ Agha said. He told Frishta I’d assist her until she passed her exams. ‘Let me know if he proves difficult.’

Did he care about my future? Why didn’t he give a damn about tarnishing my obro, pride, and ezat?

‘I don’t know if Ahmad will be able to focus on two–’

‘It’s only an hour a day,’ Agha snapped, cutting Mour short.

I had no choice but to carry out Agha’s instruction; the sooner I finished with Frishta’s studies, the better. Although Mour never opposed Agha, she might have on this occasion, had she known what was around the corner.

***

NEXT TO THE WINDOWS was her bed with brown bedlinen, brown pillows, a brown desk cloth and yellow curtains. Above it, on the wall, was affixed a postcard of two rabbits. Frishta’s wardrobe, bookcase and a Russian television stood in the corner closer to the door; like those of mine, they were all walnut – not what Frishta described: brown. This was the ordinary part of her room. The extraordinary aspect constituted owning a videocassette recorder sitting on top of the television – and waste: chocolate wrappers, clothes, books and notebooks, a cassette player with cassettes dispersed around the Afghan rug with tears. I hoped she looked after my notebooks. Mahjan needed to ask her daughter to tidy her room. But waste nappies, dirty clothes and shoes scattered in the hallway signified that both mother and daughter lazed away their time and turned the house into what Mour later called ‘a messy nursery’.

Frishta skipped through one of my notebooks.

If only I could bury my head and vanish. ‘Frishta, my friends and I see you as a sister.’ I spoke my mind in case she contemplated dirty thoughts about me.

She nodded.

‘I’ll help you if you tell no one about it.’

‘Why?’ She put the notebook next to her.

‘I don’t want to argue. This is my condition.’

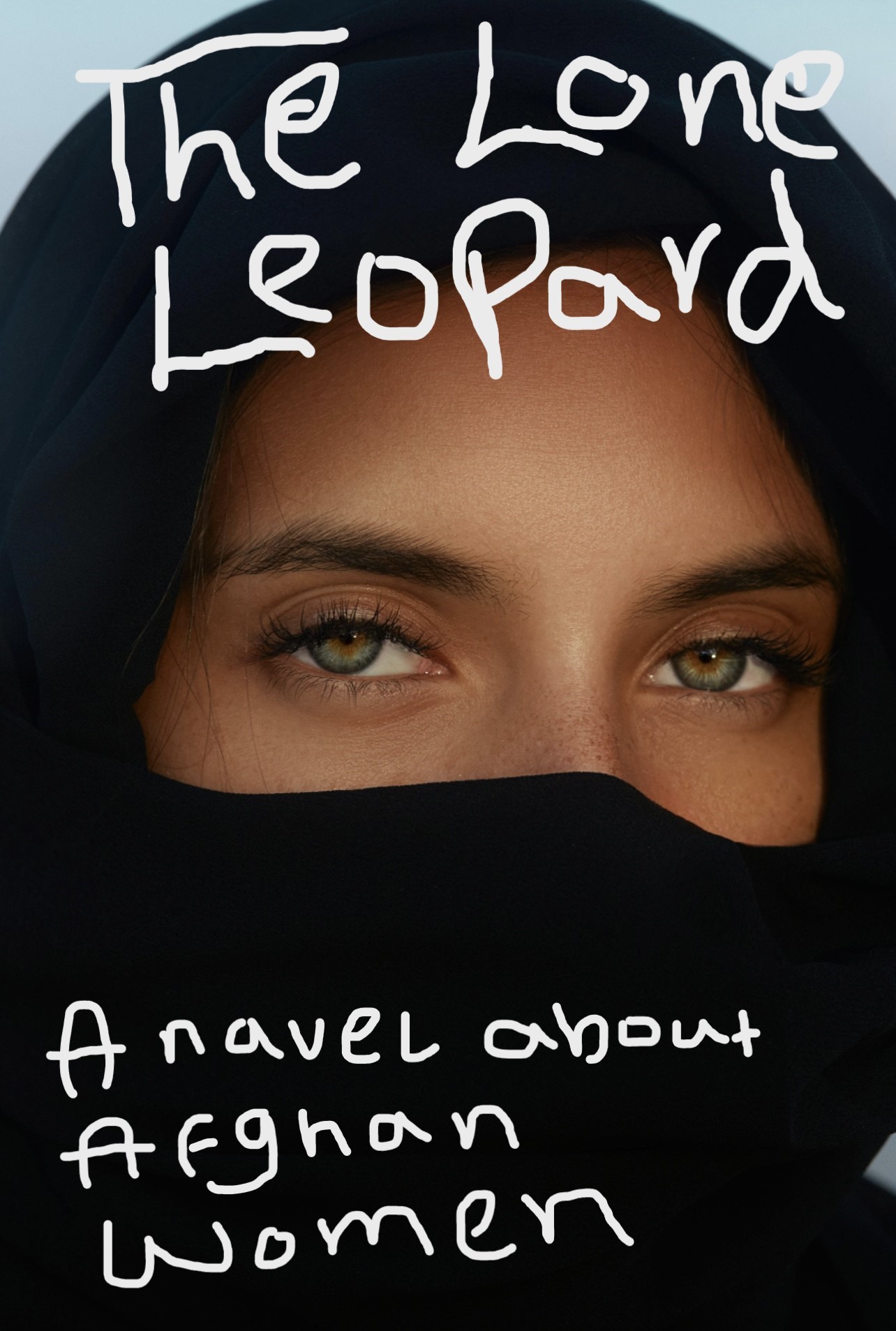

She stared at me like a leopard, an injured one; her black, red and purple eye socket appeared more so in the bright light.

‘And please don’t quarrel with Mour. It causes her a lot of worries.’ Earlier on, I saw Mour’s muscles tensing over the argument about the gym.

‘She’s ruining your sisters’ future.’

‘She knows what’s best for her daughters.’

‘She believes what’s right for her is right for everyone.’

‘Are you not guilty of the same attitude?’

She grabbed the schoolbag from her bedspread, stretched her legs out along the bottom front leg of the bed, and leaned against the wall.

I asked her about Rashid, whose return I feared.

‘The school won’t see the coward again.’ She unzipped her schoolbag. ‘Women are patient but not feeble.’ She took her green notebook out, unfolded it and put it on her lap. ‘Roya told me the coward touched ustads’ bottoms. Pulled down jelais’ skirts. The bastard forgot he didn’t drop from the sky but popped out of a woman’s womb.’ Her brown face turned darker when she spoke of him. ‘I don’t understand why you all turn a blind eye to him.’

‘Who can match Rashid? Plus, he never bothered my friends or me. And, we’re not the police.’

‘I’d rather die ten times over than see my sisters being stamped upon.’

‘And not everyone has a father in the KHAD.’

‘They have Khuda jan, though.’

‘Smell?’ Even her jasmine scent wasn’t strong enough to bury the faeces smell. No one took action when Zarghuna told them earlier on about Safi. ‘It may be Safi’s nappies.’

‘Don’t you like the natural odour?’ She smiled and rose to her feet. Sprayed jasmine and opened the window. Someone played Indian music over a running car engine.

‘Are we friends?’

‘We can’t be.’

‘Why?’ She pulled forward her white headscarf and sat in her usual place, the bangles hitting against each other with a clacking sound.

‘Frishta, I hate arguments.’

‘We’re having a discussion. I genuinely want to know why you want to keep our private classes secret, and why we can’t be friends.’

She was required to be enlightened about our culture and our religion; she’d been away from Afghanistan. According to our mosque’s mullah, educating ignorant people was a spiritual virtue. I told her we abstained from behaving in a way that people disapproved of. We didn’t want them to gossip, Khudai knows what the halek and the jelai are up to in that room. Shame on both coward families. They have no obro and ezat. Worse, don’t marry the daughters because it isn’t a decent family – the brother has a girlfriend. I wanted to be an honourable son and brother. It was enough of slander for the family that Agha drank and never went to the mosque.

She nodded. ‘Do you live for yourself or “people”?’

‘We do what custom allows,’ I said. ‘Friendship between a teenage halek and jelai is improper. Such an unnatural relationship would entrap us in scandals.’ I chose to withhold stories of how hurtful improprieties had led to countless murders and suicides. ‘On a personal level, it’ll damage my image in school. Students would call me zanchow.’ I didn’t even want my close friends to perceive me as ‘feminine’. Baktash wouldn’t care, but Wazir would disown me as a friend.

Her massive eyes widened like she’d discovered a clue to a predicament.

‘And for you, Frishta, if you hung around with me, you’dput your future marriage at stake.’ Bringing in her marriage prospects embarrassed me, but I had to instil this in her or else the ignorance could cost her honour. ‘It’s your responsibility as a woman to avoid mingling with men, or else people are quick to think filthy thoughts.’ I repeated in the hope she’d learn. ‘Ask Mour about what shame brought on the next-door neighbours in Surobi.’

‘Tell me?’ The car and its music stopped running.

‘The mother committed suicide and the father disappeared with the remaining children once the daughter eloped with a halek. A decade later the brothers slaughtered the sister, her husband and their two children to regain their stained obro and ezat.’

‘I’m not asking you to elope with me.’

‘You didn’t get the point.’

‘I get it. You’re lecturing me that I must worry about what others think of me, rather than focus on what I want for myself.’

‘I didn’t say anything about giving up your wants.’

‘You want me to suffer from anxiety?’

‘You misinterpret what I’ve said.’

‘I don’t give a damn about social pressures.’

‘Picking a war with the entire population is a sign of lunacy.’

‘Not all Afghans are conservative. Look at padar jan.’ Her padar jan and Agha listened in the lounge to Ustad Saifudin Khandan on the television singing Masooma Jan, accompanied by the sound of dhol, the double-headed drum, harmonium, tambur and rubab.

‘You said you were genuinely interested, and I explained. I don’t want to argue or “lecture”.’

‘We’re not arguing; we’re having a discussion. Tell me, did many jelais study in the same class with haleks 50 years back?’ She folded her notebook.

I hesitated.

‘It’s a discussion. I promise.’

‘No.’

‘Were women allowed to go to school at all?’

‘I don’t think so.’ I put a cassette in its case and gave it to Frishta. Stretched my legs and pushed my bottom forward on the hard rug; I needed a mattress.

‘Why?’ Frishta tossed it on the bed.

‘Why don’t you place it…’ I inspected but found no cassette holder. ‘By the videocassette recorder?’

She’d take care of it later, she said, and raised her eyebrows, adding another ‘why?’; the bruising and swelling to the eye socket looked severe.

‘Obviously society didn’t approve of it.’

‘Was King Amanullah’s decision to send 12 jelais to Turkey for their studies received well in the country?’

‘He’s one of my heroes, but I disagree with some of his decisions, including the one you mentioned.’

‘Because your conservative fellows interpreted the decision as un-Islamic and anti-Pashtunwali?’

‘I’m not conservative.’

‘Why are you against the decision, then?’

‘We didn’t have two tailors in Afghanistan, and he wanted all Afghans to wear Western dress.’

‘Point noted. Do you think, though, the decision in question contravened Islam or Pashtunwali?’

‘Pashtunwali doesn’t like a woman working outside or mingling with men, let alone studying abroad.’

‘Define Pashtunwali.’

I knew it by heart from Rahman Baba’s book from year seven. Pashtunwali guided our conduct. Stood for independence, bravery, loyalty, justice, revenge, self-respect, righteousness, pride, honour, chastity, hospitality, love, forgiveness, tolerance, faith and respect of elders.

Her eyes widened. ‘What’s Islam?’

I didn’t like this and the previous question. As an Afghan and a Muslim, she should’ve known both our sacred code of conduct and our dear religion. With such progressive parents, I quickly reminded myself, it’d be wrong to have high expectations from her. ‘Islam’s our religion based on the Quran and the deeds and sayings of our beloved Prophet, peace be upon him.’

‘I am a Pashtun – a Durrani Pashtun, even though I don’t fluently speak the language. But is it just to take away our independence? Does physically imprisoning us demonstrate courage? Where is faith if women aren’t trusted to step off their doorsteps? Doesn’t respect start at home? Don’t we as mothers, sisters, wives and, above all, human beings deserve to be respected?’ Her eyes welled up.

‘You are respected.’

Brigadier erupted with a hee-haw in the lounge.

‘We aren’t or else you’d have no issue with those jelais being educated abroad.’

I shrugged.

‘Society or “people” claim it’s against Pashtunwalito have women outside the four walls of their homes because “we’re a white cotton”’ – she touched her white tunban – ‘“and easily get stained”, right?’

I shrugged. Knew it was good behaviour for women not to venture outside but didn’t know in detail why. Never asked Mour for details. Saw no need to question the way of life our ancestors had followed for centuries.

‘If I lock you up and deprive you of an education, you’d equally become “stupid, frail, and a sex object”.’

‘Who said anything about locking up?’

‘Educate us, and we’d be neither stupid nor a sex object. Or else there wouldn’t have been a Margaret Thatcher or Indira Gandhi, or our own Malalai Anna. Did Malalai Anna not join her brothers in the Maiwand War? Was this against Pashtunwali?’

‘Malalai Anna’s case was different.’

‘It wasn’t. Anna aimed to have more Malalais struggle alongside their brothers. It’s time to rediscover Pashtunwali’s true essence.’

‘Which is?’

‘Equal treatment and respect for both men and women.’

Did she argue that women should publicly mingle with men? Wasn’t she mad? I didn’t tell her. Already explained the status quo. Up to her to accept or reject it. Wouldn’t concern me whichever decision she made.

Nazo counted in the hallway, and Zarghuna told Safi to hurry up and hide.

‘King Amanullah obtained independence from the British Empire, passed the first Constitution guaranteeing equal rights for all Afghans, promoted equal education for men and women, abolished slavery, and introduced liberal reforms. And what did we give him in return?’ Frishta asked. ‘Accused him of being a kafir and declared war against his Kingdom.’

I stood up, pushed the window with her permission, and shut out the women chatter and the muffled folk music from neighbours’ apartments; the same music played at a low volume in the lounge.

‘Because he refused to pay the conservatives’ salaries,’ she added, burying her legs in her loose orange and white kameez.

I sat back. ‘That was only one factor. He made other unwise decisions.’

‘It isn’t un-Islamic either, but certain mullahs’ interpretation of Islam made it so, just for their benefit. Was the Prophet’s wife not a businesswoman? Did Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, not encourage all to study? Did women not struggle together with the Prophet?’

Her use of Islamic and patriotic references falsified my assumption about Frishta’s ignorance. Her bookcase’s five shelves bursting with books, some as fat as the pillow resting on the walnut headboard slate, weren’t just a show-off.

‘“People” abuse our human rights daily, and we’re told to be mute or else society shuns us. Well, brave women like Malalai Anna don’t fear “people”; they mould society to their definition.’

Zarghuna and Safi screamed, and Nazo giggled.

Malalai Anna had a purpose, I told Frishta. Malalai of Maiwand tended to the wounded and provided water to the mujahideen. The brave teenager clocked the flag-bearer’s fall, and the mujahideen panicked. She grabbed the fallen flag and shouted the verse. ‘Young love, if you do not fall in the Battle of Maiwand, by Khudai, someone is saving you as a symbol of shame.’ The mujahideen shouted ‘Allahu Akbar’, Khudai was Great, and launched an attack. The British soldiers noticed her effectiveness and martyred her – on the very day which was supposed to be her wedding day. But couldn’t kill her cause: boosting her brothers’ morale won the Second Anglo-Afghan War. She turned into the nation’s ‘Anna’, Grandmother, and her grave was now a pilgrimage in Kandahar.

‘I have a purpose. I want to prove a halek and a jelaican be friends without being in a romantic relationship. I want to demonstrate that a country would be better off if a woman could gain a degree and work with her brothers to build their watan. If this loses me a husband, so be it. If Malalai Anna lost her life for her people, I’m prepared to sacrifice a future husband.’ She became defensive as if I’d personally insulted her.

I hated emotions, and sadly we suffered from it nationally. I was only describing what was and wasn’t acceptable in our culture.

‘In Moscow, men and women were best friends. Nobody accused them of anything.’

‘They’re kafir. We’re Muslim. Khudai has forbidden the two sexes to be together unless they’re blood-related or married.’ I made another try, but her darker face convinced me she’d taken everything personally.

‘They were Turkish students.’

‘We’re in Afghanistan. If I had the power, I’d get the police to imprison such minglings of the opposite sex.’

‘Why are you here with me, then?’

‘I have no desire; Agha told me to.’ I got up from the rough rug. Hated being alone with her. Hated her presence. Hoped today was the first and last tea invitation in the cold and smelly home.

She stood up. ‘I’m sorry. I got carried away. I need your help, Ahmad jan. I find science too difficult.’

Agha turned my life into hell. She spoke to me as if I was to blame for the parts of the culture she disapproved of – the parts I cherished. Unless over my dead body, my sisters would hang around with haleks. We’d marry them off as they finished school. They’d build their watan, as Mour put it, by supporting their husbands and children. I’d marry someone from Mour’s village who never went to school – someone who, when Mour told her to shut up, shut up.

I had no desire to change the world, I replied. I wanted to finish school and get into a medical university. Second, I cared less about anyone when it came to the way I lived my life. I didn’t follow the examples of successful people. My hero, Mour, had shown me the traditional way of doing things, the Islamic way of behaving. Third, women were born to be home ministers and men foreign ministers. We agreed to differ, and I pleaded with her to let the matter rest.

***

THAT EVENING FRISHTA told me she spent between ‘10 and 15 hours’ a day with books. Her book collection revolved around Afghanistan history, Islam and Europe. Like me, one of her favourites was Ghobar’s Afghanistan in the Course of History. She read books on the human rights of women, and the rights of women under Islam. Over the winter, she finished Afghan Women under Centuries of Oppression, a giant book, and it made her cry.

Since moving into the apartment she’d been ‘all day’ in her room revising for her year eight examinations. No wonder I hadn’t set eyes on her. She’d seen me playing in front of the block and was overjoyed that we turned out to be in the same class. She called me a cousin because she saw me as one, she added with a smile.

Frishta had prepared for the exams as much as she could. From then on, she needed my support. I told her I’d help, provided she accepted two more conditions.

Her eyes widened like the two rabbits on the wall opposite me.

No more discussion on women’s issues and get Mullah Nasruddin’s book out and read me a story, I blurted out. Being alone with a jelai was the most awkward moment of my life, and like a fool, without thinking, I asked for a Mullah Nasruddin’s joke.

Frishta’s lips stretched.

She flashed out the thin book from the piles of red, green and pale yellow ones.

What is politics, Mullah? asks the wife,Frishta read Mullah and Politics, sitting in her usual place, her right side leaning towards the bed’s footboard.

Do you remember how many promises I made to you before marriage? Mullah asks.

Yes.

Did I fulfil them after marriage?

Not really, says the wife.

That’s politics.

We grinned. I felt like a fish out of water.

‘I don’t know why Afghans see him as a fool. He was a wise man,’ Frishta said.

Frishta was right. Mullah Nasruddin was a populist philosopher, and I knew no Afghan who couldn’t quote or allude to a few of his funny stories. His anecdotes, often with a pedagogic nature, fit almost any occasion.

Leave a Reply