Chapter Three

My routine went like this every academic year: perform the noon prayers after coming home from school, have lunch, take a siesta, drink tea with what Mour called ‘brain food’ – almonds, pistachios, walnuts and raisins – study until the five-minute cartoon film at 18:15 on television, chill with my friends until dinner around 19:30, do my homework and help my sisters with their studies, and go to bed at 21:30. I hated the last part of Mour’s timetable – it prevented me from watching the Sunday evening movie, the only American film in a week, and it upset me more if it starred Schwarzenegger or Rambo.

The first day of the routine, coupled with the crazy jelai’s threat, stopped me from napping this afternoon. How would Agha and Mour react to her lies? My heart had sunk to my stomach. I’d been expecting a knock at the door at any moment.

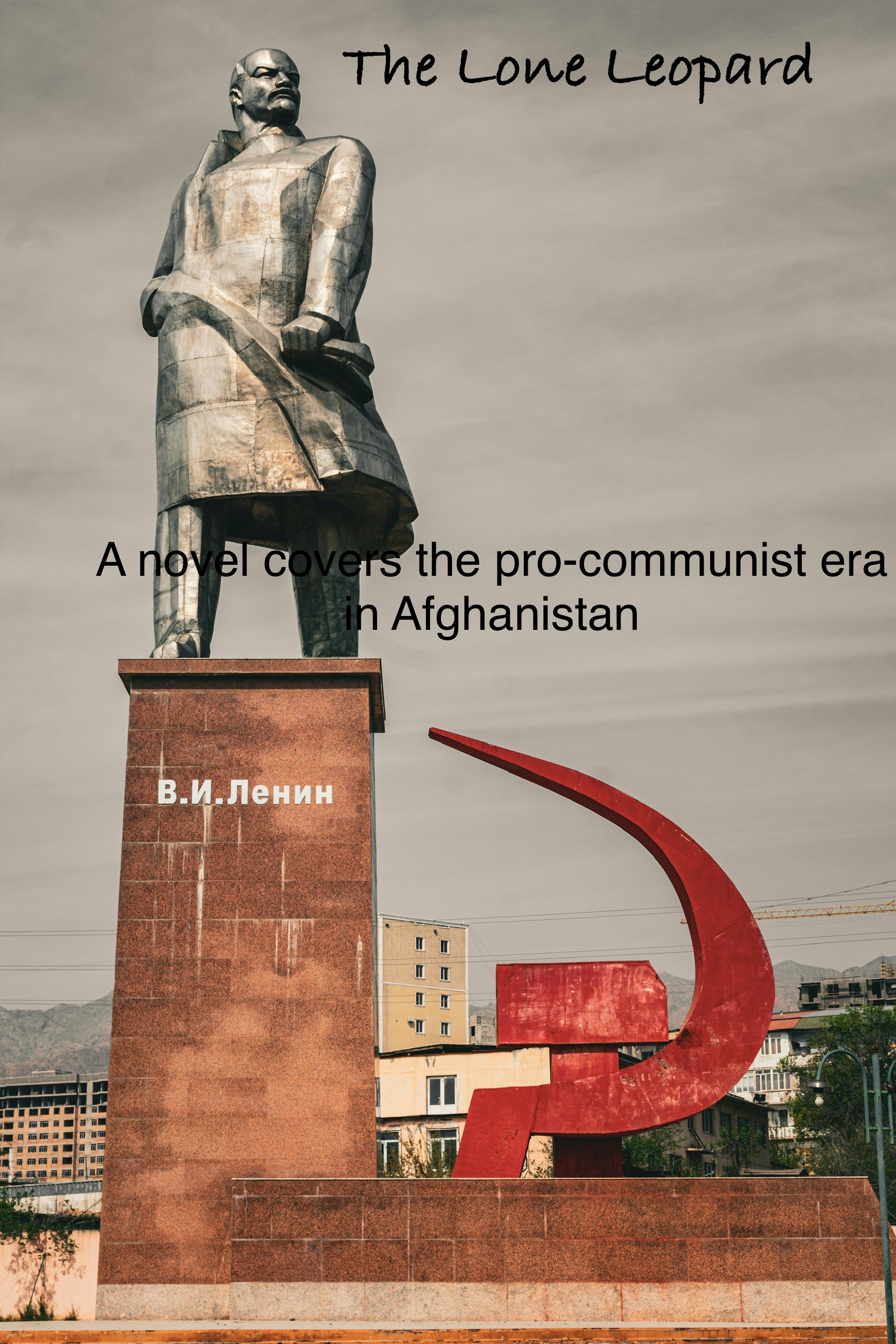

Mour required me to stay at home that day to help with new neighbours’ hospitality. A brigadier, his wife and their son had moved into the opposite apartment last week. According to Mour, Brigadier and Agha met in the notorious Pul-e-Charkhi Prison in the late 70s when President Daoud Khan locked up the pro-Soviet Communist Party leaders to thwart a military coup. But their junior-level comrades, with KGB and GRU’s secret assistance, succeeded in toppling Khan’s Republic in the April Revolution. Ever since the Parchami Agha and the Khalqi Brigadier had remained friends – their parties in power and in a constant war with the mujahideen. Brigadier served in the north, and Agha throughout the capital. Agha now arranged the transfer of his ‘trusted brother’ to Kabul and obtained a Special Order from the President for the ownership of the flat opposite that an Afghan singer and her family had vacated over the winter and ‘run away’, like most celebrities, to the West.

I overheard Agha listening in the lounge to the BBC World Service Pashto. Surprisingly, he was home earlier, maybe for the guests. Agha had two wives: Mour and his job. He had three children with Mour, and a child from his second marriage named Politics. Every day Agha left in the early morning and came back around 7:30 at night. He occupied most of his time with his other wife and my step-sibling when he was even at home, listening to the variety of news: the Voice of America in Pashto, Kabul News, Iranian Radio and his favourite and the ‘most reliable’, the BBC World Service in Farsi and Pashto. Lying on the sofa with a smouldering cigarette, he saw or heard nothing once the damn thing was broadcast. We all stayed mute. He gestured or, in extreme cases, whispered a word if he required our service. I yearned for the day Agha stepped into my room and asked how my day had been, if I liked something, or just talked about anything. Agha forgot that his other wife and three children also had a right to his love and attention.

Baktash’s father took him everywhere: to the theatre, live shows on television during Nowruzes, New Years, and Eids, and to the Soviet artists’ concerts in Kabul Nandari. Baktash told me stories of how the celebrities shook his hand and how the Tajik and Uzbek performers spoke in Dari. Some argued that he was spoiled because he was the only son; I likewise was the only halek in the family, but Agha never took my sisters or me out, not even to a shop. Even on Fridays, a family day, when many families drove to the Qargha Lake or Bagh-e Bala for a picnic, Agha was away with his other wife and son.

I once asked Agha if we all could go on a picnic on a Friday at the Paghman Gardens. My history ustad recommended a visit to our Arc de Triomphe at the entrance to the gardens, which King Amanullah had brought in foreign experts to create as part of his quest to Europeanise Afghanistan. Mour’s leek bolanis with doogh, diluted yoghurt, coupled with the monument’s visit, would’ve given us a great day out there. Agha deemed it unsafe. Safe to be a holiday retreat for the Baktashes and hundreds of other Kabuli families, I complained to Mour, but life-threatening for us. Mour shushed me, reasoning that Agha was busy providing for our livelihood. Mour never let me raise the issue with Agha again; she thought it wasn’t Agha’s responsibility.

The door knock startled me, but Mour and Agha greeting the guests in the hallway reassured me.

Tap, tap, tap at my door.

‘Tell Mour I’ll greet them later,’ I said.

My annoying sister tapped again.

‘Nazo, go away.’

Another one.

I pulled the door open. ‘Go away–’ The smiling face’s presence numbed me.

‘Don’t faint. I’m your new neighbour.’

I tried to take a breath.

‘Don’t you invite me into your room?’ She stepped in and filled the room with a jasmine aroma. ‘Wow, my favourite colour. Brown bedlinen, brown pillows, brown curtains, even a brown desk cloth. And bookcase, wardrobe, desk… All brown, brown, brown. Impressive,’ she said, raising her eyebrows. She let herself loose on my bed, her fat, round bangles hitting against one another with a clacking sound. One bangle matched her blue kameez and headscarf, and the other complemented her white shalwar.

‘Except I don’t like the layout.’ She got back on her feet. ‘I shall move the desk and chair into the corner opposite your bed… The front of the window is a bad place for the tape recorder. Move it… over the table before the bookcase next to the alarm clock… even though it isn’t easily reachable… Now my cousin’s room looks better.’

‘I’m not your cousin,’ I said, feeling tightness in my chest.

‘Who do you listen to?’ She pressed the button of the tape recorder. ‘This is my favourite Ahmad Zahir song.’ She stood opposite me and offered her right hand. ‘Friends?’

Her eyes beamed with pleasure, the cheeks glowing with redness, and the wide lips stretching to her ears. She reminded me of a mammal: a snow leopard with olive skin, a perfectly round face, large black eyes and long eyelashes. A wrestling mammal who refused to give up on its prey. Actually, she inherited a wrestler’s characteristics: plump but flexible, chubby but fit. A wrestler who dared to wrestle with a reality that was impossible to beat.

I never had a female friend. A woman never asked me for friendship. And never was a jelai alone in my room. Her presence in my room embarrassed me. How come her father allowed the daughter with a non-mahram halek? Well, if he let her stay alone in Moscow for a year, a few minutes in my room mattered little. I, on the other hand, didn’t wish to ruin my reputation. A young jelai and a halek alone in a room approximated a ticking bomb that could explode at anytime.

‘You know my answer,’ I said over her favourite Ahmad Zahir song: Life eventually ends, never submit to aggression, if the submission is a must, then it is better to die.

‘I shall tell Uncle and Aunty you’re harassing me.’ Her smile broadened under the yellowish glow of the chandelier.

‘Are you blackmailing me?’ My chest tightness got worse.

‘Absolutely not.’

‘Why do you invent lies, then?’

‘I don’t. Your father and mother are my aka and tror.’ In keeping with tradition, you called your elders from the father’s side aka, uncle; aka’s wife became akanai, not tror, aunt. But I didn’t correct the crazy jelai about the common mistake and instead took a deep breath.

Noisy chatter and waves of laughter came from the lounge. I feared Mour would open the door and see a jelai in my room. What an embarrassment. I switched off the tape recorder and rushed out of my room, into the lounge.

‘Wah-wah, my nephew has grown into a handsome man,’ a tall man with curly hair like a jungle said after I said salaam, hello, embracing my shaking body against his gigantic trunk. I felt my heartbeat against his stomach. He let go of me.

‘So handsome, mashallah.’ An obese woman with a brown face and a well-defined nose echoed her husband, using the Arabic word for ‘Khudai’s protection of me’. Did her face look familiar? ‘And I’m told he’s a well-mannered gentleman,’ the woman added, kissing me on the right and left cheeks, her strong powder foundation smell entering my nostrils.

She embarrassed me; women kissed each other’s cheeks, not men. I said salaam to their son playing marbles with Zarghuna on Mour’s precious leather sofa. The halek’s chocolate-stained hands full of marbles must’ve infuriated Mour.

The crazy jelai followed and sat next to her father, opposite Agha and me, on the three-seater sofa. My heart pounded against my chest. Brigadier half unzipped his grey tracksuit, closed his eyes and inhaled deeply. ‘I feel like I’m in Jalalabad.’

Ironically, Wazir also called our reception room Jalalabad, the capital of Nangarhar, known as ‘The Always Spring’. As in Jalalabad, Mour’s six flowerpots on the window recess smelled fresh throughout the year.

Brigadier’s wife, whom Mour called Mahjan, told me she was ‘pleased’ the crazy jelai and I were in the same class, we should be ‘friends’ and ‘look out’ for each other. Parents even abstained from small things like calling out their women’s names in public, yet the unashamed family befriended their daughter to a halek? What happened to their courage, their ezat, honour? Mahjan took her leather jacket out and asked Mour to turn off the heater. Sweat had erupted on her forehead. Now I made her out. She appeared with the celebrated actor, Haji Kamran, in comedy plays on television during Eids and Nowruzes.

Her profession and the dress style – short-sleeved green dress with leggings, and open hair without a headscarf – explained that the family was too progressive to bother about shame. Why did the crazy jelai wear traditional Afghan clothes and a large headscarf, though?

‘Except for you, zoya, Frishta knows no one in school.’ Mahjan called me ‘son’.

I looked at trays of green raisins, almonds, pistachios, dried peas, cakes and kulchas, cookies, on the black glass coffee tables before Brigadier and the crazy jelai.

‘You’re a bright student, Mashallah. Frishta needs your help,’ she added.

I counted six cow chocolates over the glass tray full of sugar-coated almonds. I neither knew the crazy jelai, nor wanted to associate with her.

‘Go and bring the notes Frishta jan needs,’ Agha said.

I stayed put, and wished Agha understood me.

‘There’s no hurry, aka jan. I can have it tomorrow,’ the crazy jelai said.

‘Raziq Khan phoned me today. We all want you to help Frishta jan. Make sure she passes her exams. Am I clear?’ Agha said.

‘Woh.’ Why did he torture me? He offered no help with my studies. On top of this, he pressurised me to share my time with a crazy jelai. I concentrated on my studies, not just for school, but also for a medical degree in three years’ time. Every year thousands of students undertook the entry assessment for a medical degree at Kabul University; only a couple of hundred got in, those who did exceptionally well at school.

‘I’m not sure if he’s got the time,’ Mour chipped in and picked up the nickel silver teapot.

‘He must make the time,’ Agha raised his voice.

Mour’s face turned red as she poured the steaming tea into Mahjan’s cup. Mour wouldn’t rescue me even if it meant I’d fall behind with my studies.

***

AFTER SEVERAL CUPS of tea, after all the news ended, after Brigadier complimentarily compared Mour’s house with ‘Munar Jada’ – a place in the heart of Kabul where hundreds of Uzbek businesses sold Afghan hand-knotted rugs; and like Munar Jada, Mour laid rugs in each of the four bedrooms, the hallway, kitchen and the balcony – Brigadier, whosecheeks were as rosy as Mour’s rugs, told us how he loved his only daughter and how he’d make her an example to the other Afghan women. ‘I give my princess the same freedoms as my Safi,’ he went on, pointing towards his son, who played marbles with Zarghuna in the corner near the bulky Russian TV set.

‘Thank you, padar jan, for not clipping my wings,’ the crazy jelai said to her ‘father’, holding Nazo’s hand.

‘One day you’ll make history, princess. I’m sure of this.’ Brigadier planted a kiss on his daughter’s head and told her how proud a father he was. His eyes, lips and whole spirit smiled at once.

The crazy jelai kissed her father on the left cheek. Did I feel jealous? I placed two sugar-coated almonds in my mouth and let them melt.

‘Once the piece of my heart becomes the Prime Minister and Zahir Shah the King, she’ll punish all Afghanistan’s enemies.’ Brigadier sipped from his teacup. ‘She’s written to the king. He’ll come to Kabul soon after the “mujahideen’s takeover”.’

The BBC reported tonight that the mujahideen captured strategic outposts beyond Khost and reportedly executed high-profile pro-Communist officials. The news predicted the fall of Kabul as ‘more likely than ever’. Recently I’d been praying to Khudai every day to keep Agha from the mujahideen’s harm.

‘I’ll have to start with those who’ve sold our watan to the Red Shorawis.’

Brigadier burst into laughter, his belly like the Bimaro Hill moving up and down.

Talking in front of the elders, and speaking in such an open manner to her father, accusinghim of selling his ‘homeland’, alarmed me. Didn’t she know Agha was a high-profile member of the pro-Communist Party?

A taqq sound. Mour told Safi and Zarghuna to play marbles by the door, the only vacant space in the room, away from her treasured TV cupboard.

‘Princess, we haven’t sold our watan. The mujahideen have.’ Brigadier’s eyes and mouth remained stretched. He asked his wife to extend her hand and turn the volume up on the television. Ustad Gul Zaman sang Oh My Homeland. I put a cow chocolate in my mouth and chewed on it.

‘Padar jan, the mujahideen defend our watan. Our religion. They look after the refugees and the poor.’

Agha’s lips pulled back. ‘Frishta jan, we defend our watan. Our reforms tackled illiteracy, gave women equal rights, offered the poor more land. We strove to protect the interests of workers, peasants and toilers. The mujahideen kill them. Burn schools and bridges. They’ve pledged to cripple Afghanistan and then gift it to Pakistan and Iran.’

Zarghuna peeked at Mour, grabbed two chocolates and offered one to Safi.

‘Aka Azizullah, the Communists invited the Shorawisto invade our watan. Afghans will never forgive them.’

‘We so-called Communists also asked them to leave, and they did. America and her puppets persist in their support to the mujahideen in Peshawar.’

‘As the Shorawis support Najibullah’s Communist regime.’

‘The Soviet Union no longer exists. It’s disintegrated,’ Agha said.

Agha shared with Mour a few months ago how everyone in the Kabul government was in anguish about its future because the new administration in Russia under someone called Boris Yeltsin had vowed to disconnect its supportive pipeline to the Najibullah regime. Like most Afghans, Agha looked to the United Nations Special Envoy, Benon Sevan, to broker a peace settlement to the 14-year civil war between the mujahideen and the pro-Communist government in Kabul. The Cold War was long over between America and the Soviet Union, but their proxies continued to fight in Afghanistan, Agha said.

‘I understand the April Revolution wanted to topple the President Daoud Republic, but I don’t comprehend why your comrades martyred his 17 family members, all children and women,’ the crazy jelai asked.

‘A mistake made in the heat of the moment,’ Agha said over one of his favourite songs, Ustad Awalmir’s This’s Our Beautiful Homeland.

‘Martyred: millions. Forced to abandon their watan: six million. Lost limbs: hundreds of thousands. Widows: tens of thousands. Political and social system: shattered to pieces. Construction: entire villages turned into dust. Has all this been done in the heat of the moment?’

‘We publicly acknowledged our mistakes and have attempted to fix them.’

‘The destruction you’ve left is irreplaceable. The Communists have crippled our watan.’

‘Afghans will one day find out who really has crippled Afghanistan, Pakistan or the Soviet Union,’ Agha said. ‘Having said that, I’m impressed by your knowledge.’

‘She reads a book every day,’ Brigadier said, making it sound like the daughter travelled daily to the moon.

I dipped a kulcha in my cup and took a bite on it.

‘Well done, zoya.’

Agha never referred to me as zoya, even though I was his real son.

‘Politics has nothing to do with religion and everything to do with interest. Powerful countries have no permanent friends or enemies, and certainly no concern for one’s religion. They’re prepared to use any means, even religion, to further their interests.’

The crazy jelai’s eyes fixed on Agha. Her father unwrapped a chocolate and threw it in his mouth.

‘America or Pakistan isn’t here for the mujahideen to help them promote Islam. We’re already Muslim. America aids the mujahideen to turn Afghanistan into the Soviet Union’s Vietnam. Pakistan assists the mujahideen to establish a puppet government in Kabul against India. The Pakistanis crave for a slave Afghanistan that’d have no ability to claim its rightful territory on the other side of the current border where our 20 million Pashtun brothers and sisters live.’

Brigadier put his left hand around the daughter’s shoulder, telling his ‘princess’ to listen to the words of ‘a wise man’, my Agha, and to read about the so-called Durand Line Agreement.

‘I know, padar jan. The British Empire imposed a border in 1893, which separated one Pashtun from the other.’

‘Afarin, hence no Afghan government has accepted it as its official border’. I heard the first ‘bravo’ from Agha, not to my sisters or me, but an ill-mannered jelai. Agha sipped his tea. I dipped the other half of the kulcha and put it in my mouth. Took a tissue and removed moist bits from my fingers.

Mour asked me to fill up the cups. Mour and Mahjan, sitting on the two-seater sofas opposite each other, listened to the debate between Agha and the crazy jelai as Afghan women always did.

‘Do you have a book on the Durand Line Agreement, aka Azizullah?’

Agha said he’d find her one.

The crazy jelai thanked Agha. ‘Manana, Ahmad jan.’ She put her hand over the cup and ‘thanked’ me.

I filled Brigadier’s cup. Counted four chocolate wrappers in the waste bowl in front of him.

‘I hope I haven’t been rude, aka Azizullah.’

‘No, zoya, you haven’t. Sadly, you were right on most things. Try to stay calm, though, when you debate your point. Hmmm…’ Agha cleared his throat. ‘The trick is to see yourself as a nursery teacher.’

Brigadier stroked the crazy daughter and advised her with a mouth full of green raisins and almonds to note another important point.

***

MINUTES LATER THE CRAZY JELAI had a quiet conversation with Nazo. ‘Medicine, mashallah,’ the crazy jelai said excitedly, her hand curling over my sister’s. Mour asked Nazo to go to bed; the crazy jelai wanted ‘some more chat’ with Nazo about school.

‘Now. It’s nearly nine,’ Mour said. Mour intended to keep Nazo away from the crazy jelai, or else our bedtime was 21:30.

Nazo peeked at Agha and put her cake-encrusted hands over her eyes. I knew she was faking it.

‘Let her stay a little longer,’ Agha said.

‘She wants to go to university and become a doctor,’ the crazy jelai said to Brigadier, her face beaming as if my sister had done her a favour by going to university.

‘Afarin,’ Brigadier said. He took a mouthful of the home-made cake and sipped his tea.

Nazo removed the crazy jelai’s hand and peeped at a glaring Mour. The crazy jelai had already rubbed off on my sister. Mour would put Nazo in place once the insane family departed.

‘We don’t send our daughters to universities,’ Mour said.

‘What about Ahmad?’ the crazy jelai said.

‘He wants to study Medicine.’

‘Ahmad can be a doctor; Nazo can’t be a doctor.’

‘Ahmad’s a halek.’

‘Everyone has an equal rightto learning.’

For Mour, words such as ‘Communism’, ‘capitalism’ or ‘human rights’ formed empty concepts which had no place in Afghan society.

‘Education helps them discover themselves. Their talents. Their identity. Helps them become an asset to their family, children and watan,’ the crazy jelai went on.

‘That’s why they go to school.’

‘Not university, though, where her future lies.’

‘Her future is in her husband’s house.’

‘I object.’

Zarghuna rolled a handful of marbles across the carpet and yelled.

‘Besides, an Afghan woman must read the Quran and learn about her traditional duties. Righteousness is more important than education,’ Mour said.

‘The first word of the Quran says, “read”, which calls on both men and women. Khuda jan wants us to learn about our Islamic and human rights.’

First Agha irritated me, and now Mour’s debate with a spoiled child. I’d rather watch An Hour With You on the muted television than have a worthless conversation with a rude jelai.

‘She’s inexperienced, but you’re the mother. Teach her. She’s putting her future in jeopardy,’ Mour said to Mahjan.

‘Why’s everyone scared of a woman’s voice?’ the crazy jelai said.

‘You must teach her the importance of respect. Life will become much easier in her real home.’

‘Tror jan, you’re insulting madar jan.’

Mahjan, the crazy jelai’s ‘mother’, frowned. ‘Frishta, your tror jan isn’t wrong.’

No Afghan disagreed that respect constituted an important concept in Afghans’ lives. The crazy jelai violated it regarding both my parents, yet she accused Mour of insulting Mahjan. Safi yelled ooh and threw a marble, hitting Mour’s crystal chandelier. Mahjan chastised him, warning she’d take him home if he misbehaved again.

‘OK, you teach me what madar jan’s neglected.’

‘Frishta, behave.’ Mahjan raised her voice, frowning.

I loathed her. Didn’t she know elders talked and juniors listened?

‘I tell Nazo and Zarghuna that life’s demanding with the in-laws. They want you to be skilled. Cook, clean, look after the young and the elderly. If not, the in-laws would curse us, the mothers, for having given them unskilled daughters. They’ll force you to learn the hard way. So, get well prepared now if you want to have a comfortable life with the in-laws. Rudeness gets you nowhere in there, I tell them, apart from subjecting you to beating. Respect is the only means to save you.’

‘Who said we’ll knock the in-laws out?’ the crazy jelai said.

‘By respect, I mean to shut up and abstain from complaints. Endure hardship with closed lips and do nothing that dishonours the in-laws. Like a dutiful Pashtun bride, carry your responsibilities quietly, and I promise you, I tell them, things would turn out good.’

‘I hope Azizullah hasn’t subjected you to hardship for making us the tea,’ Brigadier said to Mour and burst into laughter. His sweaty face reddened. Except for Mour and me, everyone else joined him.

‘Ahmad jan’s father is a diamond. But you know, brother, we live in a conservative society and have to raise our children accordingly.’

Mahjan nodded.

‘The discussion has heated the room,’ Brigadier whispered to Agha and wiped his face with a tissue. He steadied Mour’s pot with one hand and with the other opened the window. Fresh air touched my cheeks and eyes. Agha took two cigarettes out, handed one to Brigadier, lit his and passed the lighter to his trusted friend.

‘Like water, we must adapt to any object we’re poured into,’ Mahjan said to Mour after a pause, sounding like a politician agreeing with an electorate before an election.

‘I’d rather live for one day and be free than live for a hundred years and be a slave,’ the crazy jelai said.

Mour shook her head, her eyes travelling to Brigadier.

‘I’m staying out of this,’ Brigadier said and laughed, holding a burning cigarette.

‘A wise choice,’ Agha said and inhaled cigarette smoke.

‘Mour prepares Nazo and Zarghuna to be housewives, like herself, raising children and washing cutlery.’

‘Frishta?’ Mahjan glared at the daughter.

‘Daughters: imprisoned; sons: free. Is that fair?’

‘Not your business,’ Mahjan said.

‘Only women have to become slaves? Ask tror jan if she ever taught Ahmad how to behave towards his wife?’ Did her voice break? ‘On the contrary, sons are advised to beat the shit out of their wives.’

Mour and Mahjan hadn’t touched their tea. Perhaps the heated debate and the aroma of cigarette smoke spoiled their appetite.

‘Frishta jan, I’d want my daughters to be in place of President Najibullah, but I have to be realistic. Daughters need husbands for financial support. Agha and I won’t be around all the time. The best future for them is to have their own homes. It isn’t slavery to cook for their children or wash their clothes.’

‘They don’t have to get married. They’ll have their own salaries.’

‘Jelais don’t find employment even after university. Say they miraculously get employed and endure their bosses’ harassment, their salaries won’t even be enough to cover the rent.’

‘They can live with Ahmad.’

‘I’d rather have them be slaves to their children than Ahmad’s wife.’

‘Let them finish university and then marry them off.’

‘University will take away that opportunity from them.’

‘Thousands of jelais study at Kabul University?’

‘Our Pashtun families don’t marry a jelai who’s been to school, let alone university.’

‘Is my father not a Pashtun?’ the crazy jelai asked.

‘Your views aren’t for everyone. How many times do I have to tell you?’ Mahjan said to the daughter.

The orange and silver light was turned off and on. Mahjan scolded Safi to let go of the switch. He deserved a smack.

‘We need change. Lasting change.’

‘I don’t want to sacrifice my daughters’ lives for change. So please don’t brainwash them.’

‘Education is a right, not a crime.’

Mour’s brow wrinkled as her face turned to Mahjan. ‘I have to tell you the truth. With such a tongue, no suitor will ever step on your doorstep.’

‘Telling the truth is a message of Islam. A message of Afghanness. If a suitor is scared of hearing the truth, shame on them.’ The crazy jelai’s voice broke. She dashed out.

Mahjan apologised to Mour.

‘I hope this doesn’t cost us future teas,’ Brigadier said, bursting into laughter. He shook Agha’s hand and rose to his feet.

***

ONCE THEY HAD DEPARTED, Mour told Agha that the crazy family was too Westernised for us; it wasn’t wise to socialise with such a family.

‘Liberty doesn’t mean corruption,’ Agha said and puffed his cigarette smoke.

Mour put a cup on the tray. ‘Mahjan is an actor.’

‘Was an actor: a respected profession worldwide.’

‘Not appropriate in Pashtunwali, though, especially for a woman,’ Mour said. My mother lived by ‘the way of the Pashtuns’.

‘Wazir says it’s un-Islamic,’ I said and picked pistachio shells from the sofa where Brigadier had sat.

‘That halek has lost his mind. Don’t listen to everything he says.’

‘Wazir’s a good halek. Misses none of his prayers,’ Mour said and walked out with a tray full of ceramic cups and saucers.

‘Baktash’s father isn’t happy. Stop harassing Baktash. It isn’t your business if he’s Shia or Sunni. Don’t let Saudi Arabia and Iran’s proxy conflict ruin your friendship. Am I clear?’

‘Woh.’ I picked more shells and oily pieces of cake and kulchas from the rug and placed them on the tray.

‘I’ve already got enough worries on my mind.’

Mour and his children’s needs were always secondary concerns.

Mour entered and voiced her disapproval of the decision to let a 16-year-old daughter live by herself in Russia. ‘A young woman without her parents becomes corrupt like that,’ Mour added, snapping her fingers.

Agha smiled. He agreed or disagreed with Mour, I didn’t know; probably his thoughts were elsewhere, with his other marriage and its worries.

‘The daughter of Brigadier will bring shame on her family. Remember my words,’ Mour said.

Agha smiled again, observing only Khudai knew His subject’s future. Agha talked with the crazy jelai like she mattered; with us, he sounded as though every word that came out of his mouth cost him an Afghani.

‘May Khudai show no one a daughter like Frishta,’ Mour said.

‘Ameen. And a son like Safi,’ I said and wiped away chocolate stains from the TV screen.

‘Have to keep Nazo and Zarghuna away from her. She’s a bad influence.’

‘Let the jelais socialise. Overprotection is harmful.’ Agha pressed the cigarette butt in the ashtray and then pushed it along the glass table with a scraping sound.

‘With a rude jelai like her?’

‘I believe you, too, overstepped your melmastia,’ Agha said. He had a point. Not once did Mour remind them to eat the food on the tables, an essential tenet of ‘hospitality’, and one Mour never forgot regarding other guests. Showing profound respect to all guests irrespective of their backgrounds, and doing so without any hope of remuneration, constituted a critical component of national honour.

‘I had to be candid. It’s my daughter’s future.’

‘I don’t know why you’ve declared war on diplomacy,’ Agha said.

‘She wants to be a prime minister,’ I said.

‘And change the world. Futile teenage dreams. Wait until she meets the harsh world,’ Mour said.

‘Frishta is different. There’s something about her,’ Agha said.

‘What?’ I sat on the sofa. Didn’t remember Agha complimenting anyone. His comment intrigued me.

Agha wondered. ‘Integrity, I suppose.’

‘What’s integrity?’

‘Shamelessness,’ Mour said. ‘The family is not for us.’

‘I’ve known the family for years. They’re honourable people.’

After Khudai, Mour obeyed her husband. If it weren’t for Mr Right, the crazy family wouldn’t set foot on our doorstep. A dutiful wife respected her husband and cared for him: grandparents had instilled this in Mour. Disobedience meant disrespect, which had no place in Pashtunwali. For Mour, care and respect needed to be shown in action, and Agha had passed the test.

Believing in marrying someone from one’s own tribe, the Ahmadzai, Grandma married off a 16-year-old Mour to her distant cousin, Agha, shortly after the demise of my grandfather, an imam. Agha attended school during the daytime and made mudbricks nightly to support his family, including Grandma. Mour remained grateful to Agha for letting Grandma live with them and providing Grandma’s treatment in ‘her dying days’. Grandma never saw her daughter getting pregnant, and died with worries. Agha’s parents pressurised him, as many Afghan parents would, to get a second wife; Agha wouldn’t change ‘a piece of Mour’s hair with the entire women of the world’ even if it meant they remained childless forever. Three years after Grandma’s passing, Mour’s womb showed generosity and prevented another woman from coming into the marriage. Mour developed more respect for Agha – though traditions required that Mour herself would’ve got a second wife for Agha if Mour hadn’t conceived me for a few more years, Mour once told me.

After my conception, a government job arrived that was accompanied with accommodation. ‘Who’d give us an apartment in Makroryan if it wasn’t for Agha?’ Mour often said.

I wished Mour one day had complained to Agha about his lack of interest in family life. Fathers and husbands interacting with children and wives weren’t a man thing, Mour reasoned. To compensate, Mour acted as both our mother and our father. She helped me with my school studies up to year five, the level she could teach. Taught my sisters and me the Quran. Reminded us not to lose our traditional values in the otherwise liberal Makroryan. Bought our favourite clothes in the overcrowded Mandawi Bazar: mine were baggy T-shirts, light jeans and high trainers. Packed the fridge-freezer with fresh fruit juice in summer, and filled our pockets with dried berries and walnuts in winter. Cooked meat every other day. It was ‘all for Agha’ that we could afford meat; Mour tasted it ‘from one Eid to another’ when she was our age.

Mour spent every single moment of her life for the sake of her children and husband. If after Khudai Mour worshipped anything, it was her family – and the apartment. I never saw Mour doing anything but preparing the three meals, washing the cutlery and cleaning the apartment. I begged for the day Mour did something for herself. The word ‘relax’ was not in her dictionary. She’d preoccupy herself with tidying up rooms – if there was nothing else to do. She kept the apartment as clean as the mosque. That night, Mour stayed awake until midnight, tidying the loungeand the kitchen.

Leave a Reply