Review

The Lone Leopard is…ideal for fans of Khaled Hosseini, Nadia Hashimi and Christina Lamb —CEPSAF

a powerful book that tells a story I will never forget…an emotional roller coaster…an eye-opener…that has the potential to become a classic over time. —The Rest Journal of Politics and Development

a heart-wrenching, yet hopeful story of family, friendship and love set against the…conflicts of Afghanistan…an extremely good read —Bedfordshire Refugee and Asylum Seeker Support

a generous, sensitive, well-researched novel which offers an informative perspective on Afghanistan’s past…and…future. —US Studies Online

an interesting, suspenseful, and impactful story that…gradually rises in intensity and drama —The Strategy Bridge

Libraries/book clubs looking for literary fiction that can reach an exceptionally wide audience will find The Lone Leopard hard-hitting, attractive, and educational, all in one. —Midwest Book Review

a must read —Keith Shortley

thought-provoking and engaging —Review Tales

fascinating —Andrea Jones, BRASS

an absorbing…sensitive, heartbreaking, and bold…story…It touches your heart —Review Vue

heartbreaking, and engaging… a must-read historical fiction Middle Eastern and contemporary romance drama novel. —Author Anthony Avina’s Blog

An eye-opening story that saturates the mind and heart on many different levels. —Donovan’s Literary Services

a story of…young lives, teenage angst, human affinity and grief. —USSO

an eye-opener…absorbing…and revealing...I heartily recommend it to anyone who wants to ‘enter’ Afghanistan mentally and emotionally. —Jane Marriott, BRASS

an ideal choice for university courses on… South Asia and…the Greater Middle East. —CESRAN

Praise for the author’s previous book

The new book by Dr. Sharifullah Dorani… is not just another story of Afghanistan’s troubled past, but rather is a remarkable account of the country’s modern history with details, facts and figures that presents in its entirety the reasons that made Afghanistan, in spite of its ancient and rich civilization, renowned globally for all the wrong reasons. ― U.S. Studies Online

His is the art of synthesis: of letting the known, verifiable facts speak for themselves … America in Afghanistan documents forensically how the incapacity or unwillingness of the powerful to imagine the conditions of the conquered can prove devastating to the imbalances of geopolitical power… The book is most powerful precisely when the anthropological distance is set aside and Dorani allows everyday Afghans to speak… Their voice gives the book a human scale. ― Charged Affairs

The fact that Dorani spoke to Afghans from ‘all walks of life’ in researching the book is a strength that yields many of his most cutting insights… Dorani’s Afghan perspective is truly invaluable. Americans and Westerners should pay attention. ― Carter Malkasian, The Strategy Bridge

A valuable contribution to understanding the complex motivations, causes and consequences of US policy towards Afghanistan and the internal disagreements between the actors. ― LSE US Centre

The book is extremely valuable in terms of understanding decision making towards Afghanistan… Academics and practitioners can…gain an accurate and deep understanding of America’s longest war. ― Professor Rahman Dag, CESRAN International

Gives a fascinating overview on events in Afghanistan and the ‘thinking’ behind the decisions made by successive US administrations. ― Bedfordshire Refugee & Asylum Seeker Support

Dorani’s work… provides an interesting overview of U.S. political history throughout the course of the Afghanistan war. ― The Palestine Chronicle

Eminently readable… a must-read for Afghans and others alike. ― Peggy Mason, Rideau Institute, Canada

THE LONE LEOPARD

A novel by

SHARIFULLAH DORANI

S&M Publishing House

Bedford, England, The UK

Copyright © Sharifullah Dorani, 2022

Sharifullah Dorani has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this book.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organisations, places and events, other than those clearly in the public domain, are either the product of the author’s imagination, or are used fictitiously.

ISBN 978-1-7396069-0-9

(Paperback)

ISBN 978-1-7396069-1-6

(Electronic)

ISBN 978-1-7396069-2-3

(Hard Cover)

Cover design: Patricia Porter. Cover photo of a Snow Leopard by photographer Bernard Landgraf. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document [the image of the Snow Leopard] under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License” [here is the link to the licence: https://www.gnu.org/licenses/fdl-1.3.en.html].

To my parents, wife, noor of my eyes, Elham (Hamid), Husna and Raihan (Amaan), and, most notably, the women of Afghanistan, who have received nothing from the four-decade-long war but an extraordinary amount of suffering, and who continue to face discrimination on an unprecedented scale.

CONTENTS

End of Book

SELECTED GLOSSARY OF FOREIGN WORDS

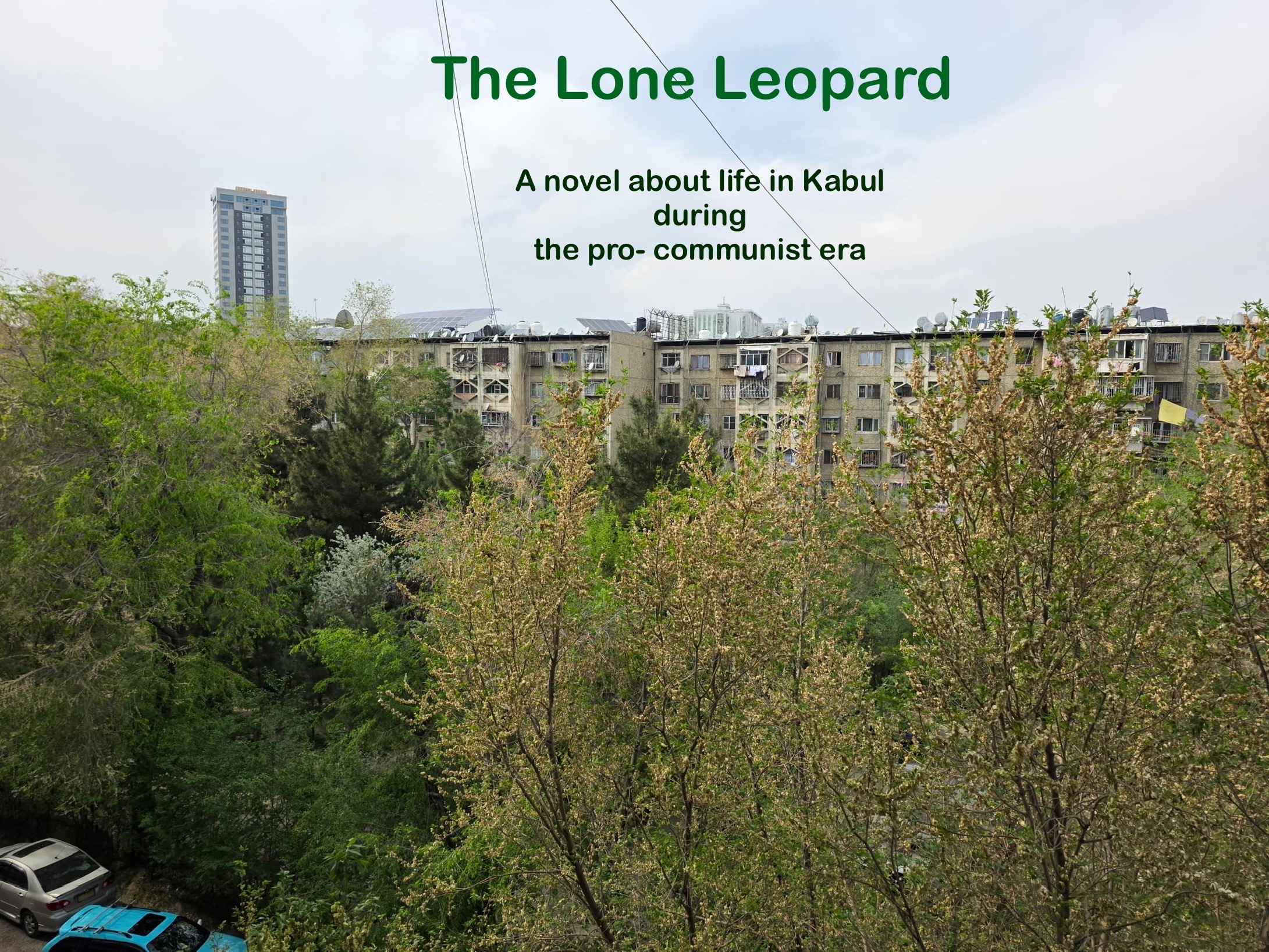

They unashamedly call it ‘Little Moscow’…

“They unashamedly call Makroryan ‘Little Moscow’”

Why did the female teachers march at the back? And who was the ‘fat man’ with a head as large as ‘the nomad’s dog’? Two questions Baktash whispered and, I bet, every student asked himself. The overweight man with a long moustache broke from the crowd and crawled up the volleyball seating stand.

‘Quiet,’ he roared, his eyes popping out like a mad cow.

All the chatting, walking on the spot and blowing on hands died down in the assembly, except the sound of drizzle hitting against umbrellas.

‘I’m Mullah Rahmat, your new mudir, and your new instructions are: follow Sharia law and stay away from lundabazi.’

My hair stood on end. How come he pronounced before the teachers the repulsive word starting with L, meaning ‘boyfriend-girlfriend relationships’? And instead of Good morning us and welcoming us back to school – or, like the old mudir, Raziq Khan, cracking a joke about how many marbles had we won or kites had we cut over the winter holidays – the new ‘school principal’ jumped into ordering us to follow our ‘religious commitments’.

‘It’s a school, not a nightclub. Anyone caught doing lundabazi, it’ll be my feet and their stomach.’

This was the first time I ever remembered someone speaking openly in school about using religion to punish immoral behaviour; the first time a mullah, an imam, heading our school instead of a pro-Communist; and the first time a mudir wearing shalwar kameez in school.

‘Why have I chosen this school?’ Mullah Rahmat asked, his eyes travelling from one corner of the assembly in the schoolyard to the other.

Silence. Everyone stood with blank faces, especially those who did nothing else but chat up jelais or young women, including female teachers. Raziq Khan, in a dark blue suit and a red tie under a black coat, cast his eyes down. He was inlove with our geography teacher, Huma jan, and so wasn’t immune from Mullah Rahmat’s threat.

‘If Kabul has turned into the capital of corrupt behaviour, Makroryan has evolved into the capital of the capital, and this school has been reduced to the capital of the capital of the capital.’

Silence. Drops of drizzle like ice cut into my face, making the first day of school even more depressing.

‘The red Russiansleft, but Makroryanis still follow their corrupt behaviour. They unashamedly call Makroryan “Little Moscow”.’

Silence. I wiped my face with my jacket and blew against my hands.

‘But I won’t allow this in my school.’ He wiped his forehead with his hand. Any jelai who complained of a halek, a young man, he warned, and he’d get his bodyguards to hang the halek from the school gate. ‘Is that understood?’

Heads nodded and mouths uttered yes. Teachers stood indignant, however. Mullah Rahmat held them liable for having transformed the neighbourhood into Kabul’s Little Moscow.

Raziq Khan was the main culprit in the school. He was a Parchami comrade of Agha, my father; like Agha, he was affiliated with the pro-Soviet People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan. Like thousands of Afghans during the past decades, the old mudir had studied in the Soviet Union and publicly promoted the Communist Union and its way of life. Raziq Khan once said if a parachutist got blown away and landed amidst the grey apartment blocks, he’d mistake it for Moscow. ‘Because Makroryan is a minor photocopy of Moscow,’ he added with a smile.

The Soviet Union had built the Makroryan apartment complex, located in the north-east suburb of Kabul, less than three miles away from Kabul International Airport. In the popular musical duo Naghma and Mangal’s song, My Beloved Air Force Pilot, on television, Makroryan from the sky looked like rows of rectangular matchboxes situated neatly behind each other in a gigantic garden full of trees and flowers. As spring set in Makroryan, as purple foxgloves, blue morning glory and pink roses in the gardens put forth new flowers and produced heavenly scents, as butterflies flew from one morning glory to another, and as the morning birds twittered and chirped in cherry blossoms, acacias and willows encircling the lawns, Makroryan was transformed into a janat: Heaven on earth.

A gardener tended the flowers and the grass in every block. The municipal officials risked losing their jobs if they left the district dry or untidy. Every other district of Kabul received electricity every other night, some even twice a week, and many electricians had their faces smashed in when the blackout happened on Thursday evenings for the weekly Indian movie; no one dared to cut off Makroryan’s electricity even for an hour. Relatives and friends from other parts of Kabul overcrowded your flat if the television showed a new Indian movie, especially if it starred the Indian legend and my favourite Indian actor, Amitabh Bachchan.

As you strolled around Makroryan on a hot summer evening, you witnessed families sitting together on lit-up garden lawns, drinking tea and listening to Ahmad Zahir or Sarban while little children played around them.

The water supply dried up in Kabul during the dry season of autumn; in Makroryan the government supplied water 24 hours a day. Kabul’s biting winters covered the city with up to 20 inches of snow, and nearly two million Kabulis struggled to afford wood and coal to heat their homes. The central heating kept our apartments as warm as a sauna. The Mirror Show on television broadcast Kabulis queuing up with their couponsand complaining that their Soviet-subsidised cooperatives had run out of this or that. Supplies were never exhausted in Makroryan; every Friday, Mour, my mother, and I saw bags of flour, cans of vegetable oil and cartons of soup lying in our cooperative. Those characteristics turned the Soviet-style apartments into a dream home for Afghan parents.

If you loitered in the area, the chances were that a secret agent from the most feared state intelligence, Afghanistan’s equivalent to the Soviet KGB, known by its acronym KHAD, stopped and searched you. If you failed to satisfy them as to the purpose of your visit to Kabul’s highly classified district, you ended up in the notorious KHAD prisons. I didn’t remember hearing an apartment being broken into or a person getting burgled in Makroryan.

The security forces had to be alert, as nearly all high-profile government officials and their families, not to mention President Mohammad Najibullah himself, and his wife and daughters, as well as most Russian advisors and their families, resided in Makroryan. Police officers guarded 24 hours a day those blocks in which Russian advisors or Afghan ministers or deputy ministers lived. Owing to Agha and the presence of a few other high-profile government members in our block, two policemen guarded it day and night.

Makroryan was also famous for its liberal way of life, and Mullah Rahmat, I reckoned, particularly alluded to this aspect. Nowhere in Kabul did there exist a swimming pool for women, but the Old Makroryan Swimming Pool opened once a week to women swimmers, and on another day of the week to Soviet citizens. Nowhere in Kabul was there a nightclub, but the Makroryan Cinema doubled up as one on Thursday evenings for Russians and Makroryanis. Every cinema in Kabul showed Indian films, but the Makroryan Cinema screened Russian movies. Nowhere in Kabul did Afghan husbands with their Russian wives amble hand in hand along the road, but you saw such couples in dozens if you took an early evening stroll to the Makroryan Market.

This so-called liberal lifestyle of Makroryan turned the district into a janat on earth for the pro-Communist haleks and jelais. Makroryan likewise constituted an earthly janat for me and countless other traditional young haleks and jelais – albeit I disapproved of its liberal nature, and agreed with Mour that something needed to be done about it. The starting point was, as Mour often said – and now Mullah Rahmat was also going on about it – good parenting. Parents needed to instil moral values in their children. Especially mothers… Someone poked my right shoulder, a signal from a friend to pay attention.

‘Can you name me a father who doesn’t drink?’ Mullah Rahmat said, glowering at us. His eyes shifted to the humming old-aged school keeper, who plodded into the concrete school building holding a shovel. ‘Quiet,’ the mudir roared when a few brave souls tittered.

Mullah Rahmat had a point. I didn’t know about the rest, but at least one-third of pro-Communist comrades I knew drank alcohol, Agha included. As Wazir once put it, a comrade was ‘less patriotic’ if he abstained from alcohol. You bought a bottle of vodka or brandy in stores in the Makroryan Market. According to Wazir, a factory in the Pul-e-Charkhi District of Kabul produced our particular brandy.

‘How many parents pray or fast?’

Again he had a point. I never saw Agha or any of his comrades stepping into a mosque or fasting. Wazir often said that a real comrade risked being seen as a traitor if they fasted. The entire district didn’t have a mosque; last year, President Mohammad Najibullah ordered one to be built by the Makroryan Market, which Wazir and I attended.

‘None,’ he said, tightening his grip on the metal stand.

Someone from the assembly coughed. Followed by another. I blew against my hands.

‘Stroll past any given block and I guarantee you will catch jelais and haleks snogging left, right and centre.’

He now told lies. Some jelais and haleks exchange love letters, but I never caught them snogging.

‘Today an Indian film is shown on television; tomorrow you shamelessly follow its fashion trends.’

I fastened the top button on my jacket to hide the Russian-style red- and white-striped T-shirt.

‘It’s our responsibility as adults, as parents, teachers and school administrators to tell our kids to follow the way of Allah.’ Drizzle drops flowed from his thick hair down past his square-shaped forehead. ‘Alas, teachers themselves copy their outfits from the unbelievers,’ he went on. His eyes rolled to Huma jan and Mahbuba jan in black coats, under which both wore the semi-official school uniform: beige leggings with a dark green outfit – a knee-length dress buttoned from top to bottom. Like them, most female teachers and deputies shielded themselves under the black, blue and purple umbrellas. Their male colleagues stood like fear-stricken chicken flock deprived of grain. Raindrops flew down their red and blue cheeks and noses.

‘The Communist regime has deviated Kabulis from Islam. Kabul must be abolished and rebuilt with an Islamic foundation.’

Raziq Khan’s eyes widened, his grey hair drenched.

Mullah Rahmat’s negative propaganda about Kabul and Kabulis equally astounded me. The new mudir dared to publicly criticise the very way of life the pro-Communist Party had fought for decades to establish. Was he too powerful for the KHAD to arrest him? Or did Mullah Rahmat ascertain that the government’s days were numbered? As each day passed the pro-Communist Khalqis and the Parchamis kept losing their grip on Afghanistan, causing Mour and me to worry more and more for Agha’s life.

Mullah Rahmat wasn’t entirely right about Kabul, though. Even in the liberal Makroryan (forget about the rest of Kabul) in Ramadan, Wazir and I scrambled for a place in the mosque to perform the tarawih prayer and recite the Quran. By the time we broke our fast after sunset, and Mour insisted Wazir ate some rice palaw and yakhni lamb, worshippers had filled the mosque. We ended up praying outside.

Someone tapped on my right shoulder.

‘Stop it.’

‘Not me,’ Wazir said.

‘Bad timing for a joke,’ I said to Baktash.

‘What joke?’ Baktash said.

‘Shall I tell the buffalo-headed mudir you’re one of the naughty haleks?’

I peeped behind and, with a sinking heart, saw a chubby jelai smiling.

‘Stop telling lies. I don’t even know you.’

‘Or shall I inform my uncle and aunt?’

‘Who?’ Jelais involved their fathers or brothers to fight harassers, never uncles and aunts.

‘Your parents, cousin.’

‘I’m not your cousin. Liar.’

‘You’ll find out.’

Goose bumps pricked my skin. I turned my face. Her unashamed smile demonstrated that she enjoyed seeing me frightened. If only the mudir would let us go to our classes.

‘Nice to meet you, Ahmad jan.’

I turned my face around. ‘How do you know my name?’ I asked, praying in my heart to Khudai, Allah, that Mullah Rahmat missed me doing the very thing he warned against. My friends overheard every nonsense she uttered. I feared they might assume I was up to something. My heartbeat increased. Please, save me from her, I prayed to Khudai, hating the jelai and her outrageous manner.

‘Friends?’ Her eyebrows were raised, her right hand stretched between Wazir and me, and her teeth chattered.

She was crazy. Instead of the white headscarf and black outfit school uniform, she wore a fluffy coat, a loose-fitting kameezand shalwar with no decorations, and a long, green headscarf. You saw no jelai wearing a traditional dress with hair fully covered in Makroryan, let alone in the school, or heard a jelai asking a halek to become her friend.

‘Friends?’ Rain dropped from her headscarf and flowed down her red cheek.

Baktash pinched me in the thigh, whispering that Mullah Rahmat might catch me talking.

‘Don’t want a jelai to be my friend.’ I turned my face.

After some more advice, linked with threats, Mullah Rahmat ended his speech by saying that he looked forward to punishing the ‘unlucky womanisers’.

Leave a Reply