Chapter Eight

The post-dinner evening teas became a nightly routine. To my surprise, Agha talked a lot to Brigadier. I soon discovered they’d fathered the same child: they sat on sofas in the top two corners of the room, opposite each other, with cups of tea and bowls of sugar-coated almonds and chocolates placed before them, and listened to the news or prattled on about politics.

Mour and Mahjan either gossiped about neighbours and relatives or talked about traditions. Mahjan had grown on Mour because she listened to, what Agha called, Mour’s ‘philosophical lectures’, never contradicted her, and, despite being pregnant, stood on her feet as part of ‘a younger sister’s duty’ whenever Mour entered the room. Mour and Frishta both made an effort to avoid arguments. Safi and my two sisters played with each other in a separate room or the hallway. Frishta stepped straight into my room, or I did into hers, depending on which family served tea.

I got to learn some striking personal information about her and the family. A Durrani Pashtun Brigadier saw a Kunduzi-Tajik Mahjan in a play in Kunduz. They got married, and Mahjan gave up acting. Frishta was born in Kunduz, but the family soon moved to Kabul, then to Kandahar. She attended school in different provinces over 16 years, owing to her father’s military work. Visiting women in the remote parts of Afghanistan opened her eyes to the plight of her sisters.

Frishta toiled for her goal: join politics and help her ‘dear watan’ and ‘sisters’. It didn’t take long before she established herself as a hard-working student. She was one of the first students to go to the board to explain the lessons, and one of the few to achieve the top grades of fives with afarinsin her non-scientific homework. Joined the voluntary work of cleaning the environment and tree planting. Stayed behind to help students with lessons. Unsurprisingly, won the Student Representative position two weeks into school, which earned her a desk in the edara, ustads and mudir’s office. And thanks to Rashid, earned the nickname of ‘the Leopard’.

Mour found it difficult to accept that Frishta secured a desk and I didn’t. I dodged voluntary school activities and social events. Spent zero time addressing students’ problems. Evaded the spotlight. Found it awkward to talk to ustads about anything apart from studies. Frishta’s grades likewise disturbed Mour. She falsely assumed Frishta stole ‘the five afarin knowledge’ from me.

Mour’s worries increased after Frishta and I shared the position of student head of the class; I for the haleks,and Frishta for the jelais. In ustads’ absence, we took the registry, went through previous lessons with students, and jotted down the mischievous students’ names. I held my hands with palms upwards and accepted the stinging blow from deputy mudir’s stick, but refused to tell on a classmate. It was only fair becausemy friends and I were the first to converse about movies, arm-wrestle or play cat and mouse.

Mour’s concerns were justified in a way. Frishta and I spent more time with each other than we did with our parents, or even our friends in the past four weeks. We hung around two or three hours in the evening, either in her room or mine. Talked about anything that intrigued us, in addition to our studies. I told her about the three Anglo-Afghan wars, about the bloody history of the Afghan kings where brothers blinded brothers, sons murdered fathers, and fathers assassinated sons just to gain the kingdom. She told me about the hardship the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, had faced throughout his life but never gave up and rose above enmity and insult. Told me stories of her ‘heroes’, the mujahideen, and how they’d bring peace and security throughout the country. Read me Shirazi, Bedil and Rumi’s poems. We analysed whether Salman Khan was a better actor or Aamir Khan, if Arnold would beat Rambo or vice versa. Discussed why the musical group of the Rain Band founded by my and Frishta’s favourite singer, Farhad Darya, split up, and which countries its singers had emigrated to; why Afghans compared Ahmad Zahir with Elvis, and if Sarban followed Frank Sinatra or Sinatra followed Sarban; or whether Michael Jackson’s automatic bed was bigger and better than President Najibullah’s one. Gossiped about classmates and ustads. Listened to Ahmad Zahir, Farhad Darya, the Kumar Sanu and Alka Yagnik duet, Modern Talking, and Frishta’s beloved album, Grease. And my favourite of all, watched movies at low volume on her videocassette recorder.

Politics and women’s issues put aside, we had plenty in common, especially history. I’d deny she was my friend if you asked me about our relationship, but she was as close as Wazir and Baktash. Those times I experienced awkwardness in her room had vanished. Her presence put me so at ease I forgot if she was a halekor a jelai. All day, every day I looked forward to our one-to-one evening classes.

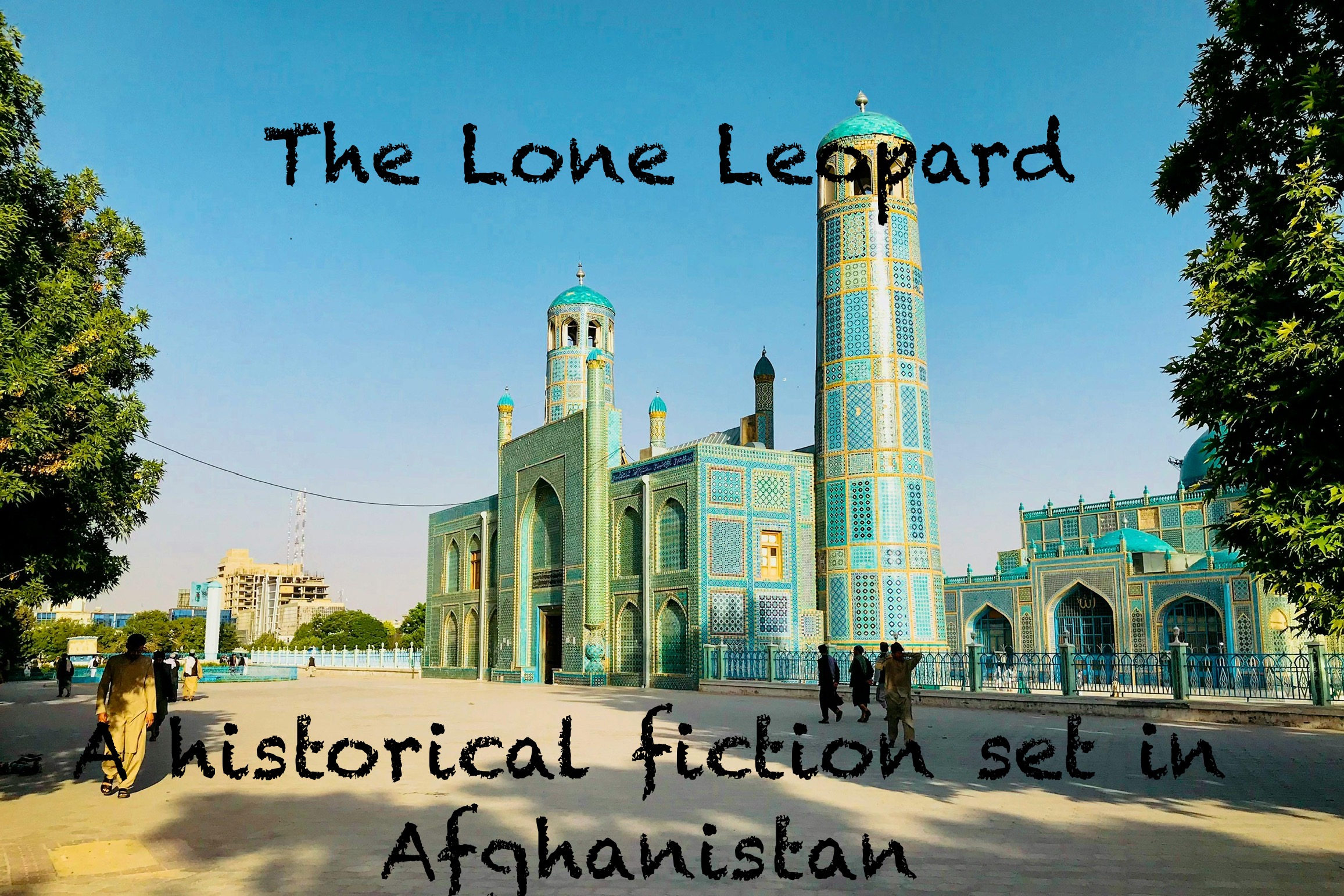

Apart from one time, we didn’t argue either and guess what? – it centred on politics. When Mazar-e-Sharif fell to the mujahideen and General Abdul Rashid Dostum, a strong Uzbek commander from the north with thousands of armed militias, Frishta predicted the mujahideen could anytime capture Kabul. I shared my anxiety that the mujahideen would kill Agha, her father and all those with high-profile jobs in the Najibullah government. Frishta reasoned the mujahideen would invite King Zahir Shah from exile in Italy, forgive everyone, and again establish a genuine parliamentary democracy like the 1960s. She accused me of supporting the kafir Communists when I doubted her rationale.

The clear-headed King reigned from 1933 to 1973, during which time no bomb went off and no rockets hit the city of my birth. Afghans went to different cities for picnics, and the streets of Kabul, the Bride of Asian cities, embraced thousands of Western tourists. I prayed Frishta turned out to be right, and the great man led us once more.

***

ON THE LAST EVENING of our fourth week, Mahjan placed a plate with four potato bolanisand a bowl of yoghurt on the rug before me, demanding I finish them off. At Frishta’s request, she switched off the muted newsreader in a tie and suit on the television and exited, shutting the door behind her.

‘Madar jan loves you,’ Frishta said, her right side leaning to the bed footboard as usual.

‘She’s filled the place of a tror I’ve never had,’ I said. Mahjan made no secret of her motherly love for me. Spoiled me with a variety of food. Once she discovered the hard rug caused me tailbone pain, she placed a mattress against the wall. ‘Mour says she shouldn’t move too much.’

‘Scientifically, it’s good for the mother and foetus to be active.’

‘I can’t eat all this,’ I said, pushing the bolanis plate closer to her.

‘In America, people eat all of them.’

We both giggled.

Frishta mimicked our English ustad, who always said in America people did this and that, and why didn’t we follow suit? Anything we did that the Americans didn’t do was wrong, and anything the Americans did and we didn’t do was equally wrong. Frishta possessed a unique talent for collecting gossip about ustads, and she shared them with me.

‘I need a knife and a fork.’ I teased her.

‘I’ll say the same: Khuda jan has given you hands, use them.’

We both giggled.

‘In America, people eat with spoons.’

Frishta’s face brightened and the corners of her mouth turned up. ‘I forgot to tell you what she said to me yesterday in the edara.’

‘Go on.’ I bit into the hot bolani and sipped yoghurt from the bowl.

‘You’re already laughing.’ She put her pencil on the notebook.

‘Say it in her voice.’

‘No.’

‘Frishta, you know I get what I want.’ She hardly refused me something when I insisted. I took another sip of the sour yoghurt.

She smiled. Frishta bent herself, twisted her face and extended her head to me. ‘In America you don’t hold the air in your stomach, Frishta jan. You let it go and enjoy it. Nobody cares. Here, we keep it tight until we burst–’

I told ustads wouldn’t converse about farts, and rolled around the floor.

She broke out into laughter, her face beaming like the bright chandelier hanging from the ceiling. ‘You’d be surprised. Ustads talk about some weird stuff.’

‘I don’t think she’s ever seen America.’

‘She hasn’t been anywhere beyond Kabul.’

‘This time, ask her whether she lunched with Bush.’

‘She’ll say he invited her, but she turned down the invitation.’

We both burst into laughter.

I initially perceived Frishta as a cry-baby, but she turned out to be hilarious. She’d win an Oscar if she tried acting. Frishta also demonstrated her trustworthiness: she kept her word about our meetings – nobody knew about them.

The family likewise grew on me. Her parents loved her, but weren’t overprotective. The danger of this or that didn’t stop them from living a normal life. They lived as if Nowruzes and Eids were the same; as though rockets had no existence.

My parents no longer took us to Surobi owing to Mujahideen’s fear. We no longer visited friends and relatives in Eids for fear of rockets. Most friends and relatives had vanished anyway. Abandoned Kabul for Russia, India and the West. Gone were the Nowruzes when Mour and her female relatives and friends stirred samanak, the wheatgerm, played dayereh and sang Nowruzi songs. All you felt was being left behind; left behind to be eaten by the soon-to-be-loose zombies.

Leave a Reply