Chapter Fourteen

It’d been two and a half hours since Frishta had entered a mud house. The day had turned into a moonful night, and, like a fearful shepherd standing on guard for the wolf’s arrival, I waited impatiently by the corner of a dirt alleyway with a thin stream dug along it. Open, smelly drains, serving as gutters, came across from each muddy house and joined the narrow stream on the passageway.

Frishta stepped out at last and glanced right and left. Locked the padlock and darted off. Startled as she turned the corner. ‘Have you been tailing me?’ Her tone conveyed more disappointment than anger.

‘What were you doing in that house?’ My heart pounded against my chest.

‘None of your business.’ She shook her head and strode off, holding a bag in her right hand and a red notebook in the left. A woman in a burka, carrying a tray of pleasantly smelling fresh naans with one hand and a little jelai with another, passed, staring at me.

‘Of course it is,’ I said as I caught up with her by the end of the stench-smelling passageway.

She paused and turned around. ‘Who are you? My father, mother, brother?’

She had a point. I was nothing to her. We’d formed a trusting relationship, but I just struck another blow to it. I looked deep into her eyes, and they expressed only one message: how badly I’d let her down. In a sick way, hurting her felt good.

‘Look, Ahmad, by now you know perfectly well I’m not one of those women who’re told what to do. I was born free and will die free.’

‘What’s the notebook about?’

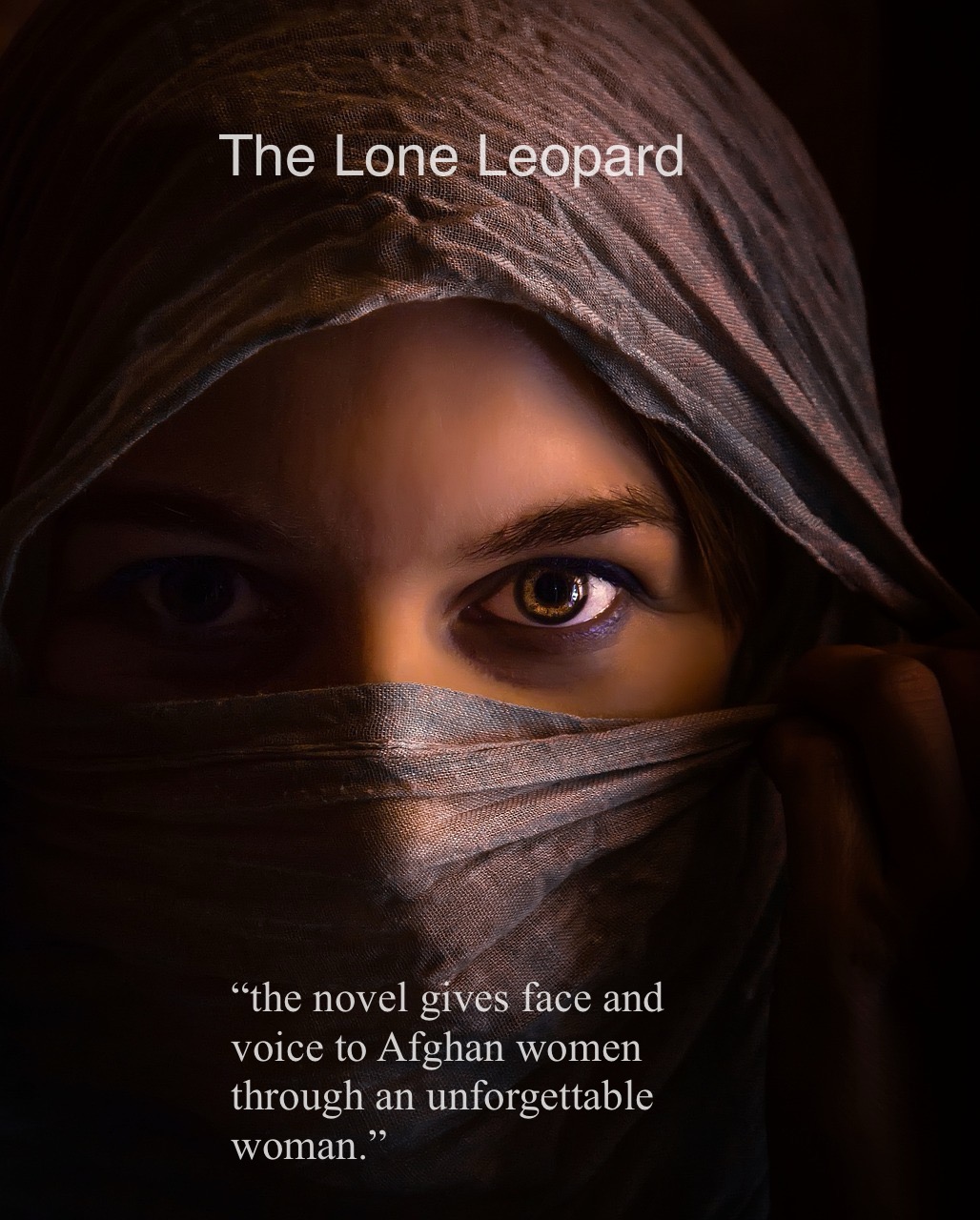

‘Stop asking me bleeping questions.’ She adopted a guarded stance – more Taekwondo than judo – staring at me like an angry leopard. She was scary.

I checked around. Thankfully, no one was about apart from an older man holding a toddler’s hand walking on the barren land with sporadic thorn bushes. She dropped her guard after a few moments and carried on walking, shaking her head. Guarding against the trusted person in her life pained even more.

I didn’t know what to do. Part of me believed she’d betrayed me. The other part, the sensible one, reasoned that she rightly claimed she was a free person and chose where she wanted to go. Couldn’t she have informed me about it, though? As one of the closest persons in her life, did I not have the right to know about her relationship? Couldn’t she just say she wasn’t an accomplice in the love letter business if she was innocent?

A fire burned in my stomach for the truth. The anguish of not knowing was unbearable, especially her alleged relationship with Shafih. I knew I couldn’t get anything out of the stubborn Frishta, so the red notebook, something I never saw before and over which she became defensive, could offer all the answers. Maybe it was an album of photos of Frishta and her lover.

I ran against the dusty wind and caught her by the barren land closer to Airport Road. ‘I’m entitled to know about your business in that house. I’m your mina. Remember you admitted it in front of the whole school,’ I heard myself say, to my disgust.

‘I don’t want a piss pants to be my mina.’ She stood on guard again.

The words ‘piss pants’ went through my heart like a sword. ‘I understand, I’m not your mina. Your mina lives in that house. It’s the ugly Shafih?’

‘He’s more handsome than you are.’

‘Is that why you helped him with the letter?’

‘What can you coward do if I did?’

‘I trusted you, Frishta. But you’ve proved you really are a harami,’ I said, feeling as if I had thrust the thorny bush behind her into my stomach by calling her ‘bastard’.

She froze. Wanted to say something but struggled to open her mouth. Her eyes locked on my eyes. I had no idea what damn thing she sought out in them. She burst into tears as though she discovered both her step-parents had just died. ‘Don’t ever talk to me again.’ She collected herself and carried on walking on the uneven ground.

I had a sudden compulsion to do something but decided against it. Then, to my horror, found myself sprinting and snapping the red notebook. Her bag’s content flew and scattered on the dirt ground, making a mixture of clinking and clattering sounds.

I flew off.

The chubby Frishta stayed put. Didn’t even utter a negative word. Only pleaded to return the notebook if I had any respect for her.

I carried on sprinting and, after crossing Airport Road, hid behind a muddy shed in the green land from where Mour often dispatched me to get fresh milk and vegetables. Peeked. Frishta froze on the dirt ground, lost in thoughts like a widow with starving children. Crushing her down purified the miserable feelings I’d gone through. She betrayed me. The agony of not ascertaining her business in that dirt house, and her connection to the love letter, choked me to death. Poked my head. Still on her knees, picking up the scattered crockery and cutlery.

I headed for a construction site in Makroryan. Climbed over the wall and jumped in. Sat on the cement bags on wooden plates with Russian lettering, situated between two cranes, as high as the sky. In trepidation, flicked open the first page of the red notebook in the full moon and saw the drawing of a white pigeon. Flicked another page and read, ‘The Diary of Frishta Gharibdost’, ‘Loving the Poor’. Skimmed through more pages and, to my horror, found everything in Russian. I recognised the alphabet because Raziq Khan had acquainted us with the letters when he doubled as a Russian ustad. But the letters were all I knew about the Russian language. Turned more pages in desperation, but apart from the few words that introduced Frishta’s diary, found nothing else in Dari.

The illuminating moon enfolded my attention. I once read in a book that the moon didn’t fight. It attacked no one. Didn’t worry and posed no questions. Remained faithful to its nature, and its power never diminished. I envied the moon. I betrayed my nature and bit my loyal friends. Posed questions I had no business with. Questions that ate me from within, especially after she didn’t deny Shafih was her halek and hinted at helping him. I’d believed her diary might answer those questions, but it didn’t defuse one bit of my anxiety. Wanted to scream but decided against it. I knew our closeness belonged to the past. Three days ago I lost my reputation; today I lost Frishta. This time for good.

I felt more tired than I’d ever been before, as though the two gigantic cranes weighed on my shoulders. Wanted to stay on the rough bags with a mixture of cement and grease odour forever. Didn’t want to return to the world where I was known as a piss pants, where people perceived me as a sinful lover; a world which Frishta was no longer going to be a part of. I’d lost a trusted person forever. Or was she trusted anymore? My head was exploding for not learning the truth. I couldn’t believe I stole her diary. Worse, I fell to the lowest of the low by calling her a bastard. Taunted her with the very secret she’d shared with me. Did she not mock me, though, calling me a coward? Was she not meant to keep the secret? Yesterday she said people forgot, but today she called me a piss pants. She used words she knew bit me like a snake.

I closed my eyes, wishing Khudai took my life. I loathed myself even more. The place calmed me down somehow. None of these precast concrete walls of flats, balconies and windows recognised me as a piss pants. They had no knowledge about the wicked letter. Didn’t know I was a thief, a cowardly one. Had no tongue to taunt me. No soul like Frishta to deceive me.

My eyes opened when the thought of tomorrow crossed my mind. How would Brigadier react to stealing his princess’s diary? What about Mour and, of course, Agha, who’d warned me against a complaint from Frishta? Importantly, what about Frishta? I didn’t want to think. A few days ago I was the trusted person and a good child whom everyone was proud of; today I became an embarrassment, even a thief, and let everyone down. How years-old reputation could shatter into pieces in a day.

I tucked the diary into my jeans and sprinted home.